A Taste of Nested Classes, part 1

In the recent posts I mentioned that because of class nesting the receiver of an implicit-receiver message send is not necessarily "self". The full story with a comparison to other approaches is told in Gilad's paper On the Interaction of Method Lookup and Scope with Inheritance and Nesting. In this series of posts I provide an informal example-oriented introduction for someone familiar with Smalltalk, to help better understand the full story.

First an important terminology note. When we say "class" we can refer to either a (textual) class definition or a class metaobject. Because the relationship between the two in Smalltalk is normally one-to-one, we can pretty much ignore that ambiguity. The Newspeak situation is different, and not thinking of definitions and metaobjects as separate things is perhaps the easiest way to get confused. To avoid that, in this post I'll stick to spelling out "class definition" or "class metaobject" fully, unless there is no danger of confusion.

Quite naturally, "nested classes" first of all mean nested class definitions. Why would we want to nest one class definition inside another? This, of course, largely depends on what exactly such nesting translates to and what benefits it brings, and that's what this whole series is about. For starters (even though this by far is not the primary benefit) let's assume that we do it as a matter of code organization. For example, suppose we are implementing the immortal Asteroids game and decide to nest the definition of the Asteroid class inside the Game class. In the current Newspeak syntax it would look something like this:

class Game = ()

(

class Asteroid = () ()

)

This rather basic implementation will not bring us hours of gaming enjoyment, but at least we do now have one class definition nested inside the other. How do we work with this thing?

Starting from the outside, in the current Newspeak system hosted in Squeak, this definition would create a binding named "Game" in the Smalltalk system dictionary, holding onto the Game class metaobject. This means that in a regular Smalltalk workspace we could evaluate

Game new

and get an instance of Game.

I want to emphasize right away that despite what this example may suggest, Newspeak has no global namespace for top-level classes. This availability of Game as a global variable in Smalltalk alongside the regular Smalltalk classes is the scaffolding, useful here to write examples in plain Smalltalk to keep things more familiar for the time being.

So what about Asteroid---how could we instantiate that one? Nesting a class in another essentially adds a slot to the outer class definition, with an accessor to retrieve the value of the slot. That value is the metaobject of the inner class. So, we get an inner class (metaobject) by sending a message to an instance of its outer class (metaobject). Notice that it's not "by sending a message to the outer class"--- "an instance of" is an important difference:

game := Game new.

asteroidClass := game Asteroid.

asteroid1 := asteroidClass new.

asteroid2 := asteroidClass new

So far nothing really surprising, apart from having to go through an instance of one class to get at another class. Let’s now change the example:

class1 := Game new Asteroid.

class2 := Game new Asteroid.

asteroid1 := class1 new.

asteroid2 := class2 new

This is more interesting. asteroid1 and asteroid2 are both instances of Asteroid and behave the way the class definition says. But since the Asteroid class references come from different game instances, what can we expect beyond that? For example, what would these evaluate to:

asteroid1 class == asteroid2 class

asteroid1 isKindOf: class2

The answer is false, for both of them. The two instances of Game produced by Game new evaluated twice contain independent Asteroid class metaobjects. Their instances asteroid1 and asteroid2 are technically instances of different classes, even if those metaobjects represent the same class definition. (Relying on explicit class membership tests is a poor practice in Smalltalk, and this illustrates why it’s even more so in Newspeak).

Let’s now look at another variation:

game := Game new.

asteroid1 := game Asteroid new.

asteroid2 := game Asteroid new.

In this case

asteroid1 class == asteroid2 class

is true because the two sends of the message Asteroid retrieve the same Asteroid class metaobject held onto by the instance of Game.

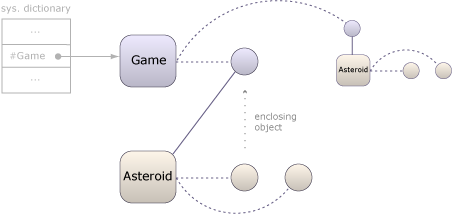

Let’s now summarize the objects involved and their relationships. They are shown in the following picture

There is a class metaobject for the Game class, contained by the system dictionary (shown in gray to emphasize that it’s not an “official” part of the scheme). An instance, connected to the class with a dotted line to represent the instance-of/class-of relationship, holds the Asteroid class metaobject. That metaobject has instances of its own, which are the asteroid1 and asteroid2 of our example.

If the Game class has additional instances (one such instance is shown small in the diagram), each instance has its own copy of the Asteroid class metaobject. If there were multiple levels of nested classes, the scheme would repeat for the deeper levels.

The diagram also illustrates a concept that will be central to the next part of this series: the enclosing object. In terms of our example, an enclosing object of an asteroid (instance) is the game (instance) that owns the class (metaobject) of the asteroid. This relationship is obviously quite important and useful: simply put, it means that an asteroid knows what game it is a part of. That’s simply by virtue of nesting the Asteroid class definition inside Game, without having to explicitly set up and maintain a back pointer from an asteroid to its game.

(Continues in part 2).